EXCAVATIONS

The Cappadocia Gate

The

cutting of the section across the entire width of the gate passage

(Figs 13

and 15) revealed

that it would have been possible for wheeled vehicles to pass

through the gate only during the Iron Age. Immediately after

the fire, in or around 547 BC, the gate was deliberately destroyed.

At some later date, perhaps in the Byzantine period as suggested

by pottery sherds, part of the rubble fill of the passage was

removed so as to make a track fit for animals. A battered pile

of stones was used to retain the very loose rubble fill on the

western side of this narrow track. It is now clear, therefore,

that the wide and prominent road that climbs gently up the hillside

to the Cappadocia Gate is an Iron Age road. The floor of the

gate passage was unpaved, the eroded Iron Age surface of the

passage being covered with charcoal fragments from the city's

destruction.

Other

work at the gate (Fig.

14) was carried out in preparation for more extensive

clearance and conservation in 2003. When this program is completed,

the Cappadocia Gate will provide a focal point with strong visual

impact for a growing number of visitors.

FINDS

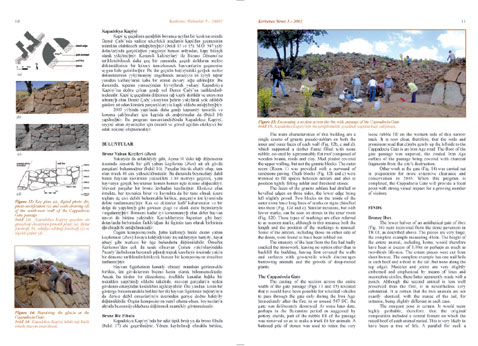

Bronze Ibex

The

lower halves of an antithetical pair of ibex (Fig.

16) were recovered from the stone pavement in TR 01, as

described above. The pieces are very large, the complete example

measuring 41cm. The height of the entire animal, including horns,

would therefore have been in excess of 1.00m or perhaps as much

as two-thirds life-size. The extant pieces were cut from sheet

bronze. The complete example has one nail hole in each hoof

and a third in the tail (but none along the top edge). Muscles

and joints are very slightly embossed and emphasized by means

of lines and incomplete circles, these latter apparently made

with a punch. Although the second animal is less well preserved

than the first, it is nevertheless very substantial. It is certain

that the two animals are not exactly identical, with the stance

of the tail, for instance, being slightly different in each

case.

The

rampant pose is certain. It would seem highly probable, therefore,

that the original composition included a central feature on

which the raised hoof of each animal rested. This is very likely

to have been a tree of life. A parallel for such a composition

that is not far distant from Kerkenes, and perhaps not very

much later in date, can be seen on the decorated terracotta

tiles from Pazarli near Çorum.

It

is possible, but by no means certain, that the animals were

winged. Such an arrangement would perhaps go some way to explaining

why the extant pieces end across the middle of the torso, particularly

if the wings were made of a different material. It is likewise

possible, but by no means necessary, to imagine that both animals

were looking back over their shoulders rather than facing forwards.

Whatever the original composition, it seems more than reasonable

to assume that the horns were emblazoned with gold.