| |

THE

URBAN SURVEY

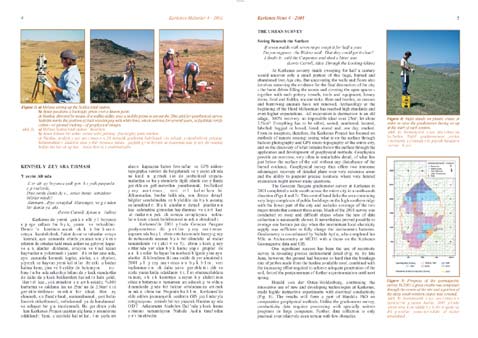

Figure

3 :

(3a)

Melissa setting up the Sokkia total station.

(3b)

Aysun positions a backsight prism over a known point.

(3c)

Nurdan, directed by means of a walkie-talkie, uses a mobile prism

to set out the 20m grid for geophysical survey. Sadettin marks the

position of each wooden peg with white lime, which survives for several

years, to facilitate verification - or ground truthing - of geophysical

images.

Figure

4: Nufel stands on plastic crates in order to raise the gradiometer

during set up at the start of each session.

Figure

5: Progress of the geomagnetic survey. In 2001 a great swathe

was completed through the centre of the site and a portion of the

steep south-western slopes was covered.

Seeing Beneath the Surface

'If seven maids with seven mops swept it for half

a year,

Do you suppose', the Walrus said, 'That they could get it clear?'

'I doubt it,' said the Carpenter, and shed a bitter tear.'

(Lewis Carroll, Alice Through the Looking-Glass)

At Kerkenes seventy maids sweeping

for half a century would uncover only a small portion of this huge,

burned and abandoned Iron Age city. But uncovering the walls and floors

also involves removing the evidence for the final destruction of the

city - the burnt debris filling the rooms and covering the open spaces

- together with such pottery vessels, tools and equipment, luxury

items, food and fodder, ancient ticks, fleas and beetles, as erosion

and burrowing animals have not removed. Archaeology at the beginning

of the Third Millennium has reached high standards and even higher

expectations. 'All excavation is destruction' is an old adage, '100%

recovery' an impossible ideal over 25m2, let alone 2.5km2! Everything

has to be sifted, sorted, numbered, located, labelled, bagged or boxed,

listed, stored and, one day, studied. From its inception, therefore,

the Kerkenes Project has focused on methods of remote sensing: seeing

what is on the surface through balloon photography and GPS micro-topography

of the entire city, and on the discovery of what remains below the

surface through the application and development of geophysical methods.

Geophysics provide an overview, very often in remarkable detail, of

what lies just below the surface of the soil without any disturbance

of the buried evidence. Geophysical survey thus offers two immense

advantages: recovery of detailed plans over very extensive areas and

the ability to pinpoint precise locations where very limited excavation

might answer many questions.

The Geoscan fluxgate gradiometer survey at Kerkenes in 2001 completed

a wide swath across the entire city in a north-south direction (Figs

4

and 5).

This central band links the area containing very large complexes of

public buildings on the high southern ridge with the lower part of

the city and includes coverage of the two major streets that connect

these areas. Much of the 2001 survey was conducted on steep and difficult

slopes where the rate of data collection is necessarily slower. It

nevertheless proved possible to average one hectare per day when the

intermittent local electricity supply was sufficient to fully charge

the instrument's batteries. Gradiometry is co-ordinated by Nahide

Aydın, who completed her MSc in Archaeometry at METU with a thesis

on the Kerkenes Geomagnetic data and GIS.

One significant success has been the use of resistivity survey in

revealing precise architectural detail (Fig. 6).

By late June, however, the ground had become so hard that the breakage

rate of probes made from the hardest available steel, combined with

the increasing effort required to achieve adequate penetration of

the soil, forced the postponement of further experimentation until

next spring.

Harald von der Osten-Woldenburg, continuing the innovative use of

new and developing technologies at Kerkenes, made highly instructive

experiments with electrical conductivity (Fig. 8).

The results will form a part of Harald's PhD on comparative geophysical

methods. Unlike the gradiometer survey, conductivity data requires

processing with specially written programs on large computers. Further,

data collection is only practical over relatively even terrain with

few obstacles.

|

|